It’s been a while since I posted something on the topic of actual shoemaking rather than just showing off finished products, and we’re long overdue. I’m going to talk a bit about currying leather.

It’s not what you think – I’m not going to the Indian market to pick up the proper spices. Nor am I performing a mathematical transformation of a function with multiple arguments into a chain of functions, each with a single argument. In fact, the verb “to curry” is actually much older, and comes from the 13th century, from the Middle English currayen, from Anglo-French cunreier or correier, which was to prepare, curry, from Vulgar Latin conredare. It means to dress tanned hides by soaking, scraping, beating, etc. in order to make them supple and resistant to water. So, how does one do this, exactly? First, a history lesson…

The Great Leather Act of 1603 (adopted in US in the later 1600s through the 1770s), forbade UK shoemakers from currying or finishing their own uppers. In order to ensure that the members of one guild were not practicing an art which was under the umbrella of another, regulations were often put in place to limit certain activities. The most relevant example is likely Richard II’s 1395 Indenture of agreement between the Cordwainers and the Cobblers. It was “…made unto our Lord the King by the Cobelers [cobblers, the workers of old leather]…making assertion that they could not gain their living as they had gained it theretofore, by reason of their disturbance by the Wardens of the trade of Cordewaners [cordwainers, workers of new leather]…”

In any event, when using vegetable tanned leather for uppers, it should be properly curried. That is, it should have various fats and oils imbued into the leather to render it supple, and resistant to cracking or tearing. I must admit that I am late to the game in this, as I’ve not treated my upper leather in this manner previously. Considering the fact that reenactors as a matter of course do not tend to use their shoes every day, that is likely the reason that I have gotten by for so long without doing it. However, I recently noticed that a pair of boots that I made a while back has shown some cracking. This is normally due to leather drying out and being robbed of its moisture and oils. The currying process helps to prevent this.

Marc Carlson, in his section on leather, indicates that impregnating vegetable tanned leather with grease or oil by working it into the skin (i.e. currying it!) can make even relatively stiff leathers supple and pliable. The master of the shoemaker’s shop in Colonial Williamsburg indicates that applying an oil such as whale oil or more preferably, cod liver oil, and setting it aside afterwards for about a month will cause the leather to oxidize somewhat, rendering a stiff leather more supple. Then, after a while, tallow can be used to give it a nice waxy feel. The entire description of the process at the Crispin Colloquy is actually quite fascinating, and I strongly suggest reading the full post. Sources for cod liver oil and tallow are also given in the post.

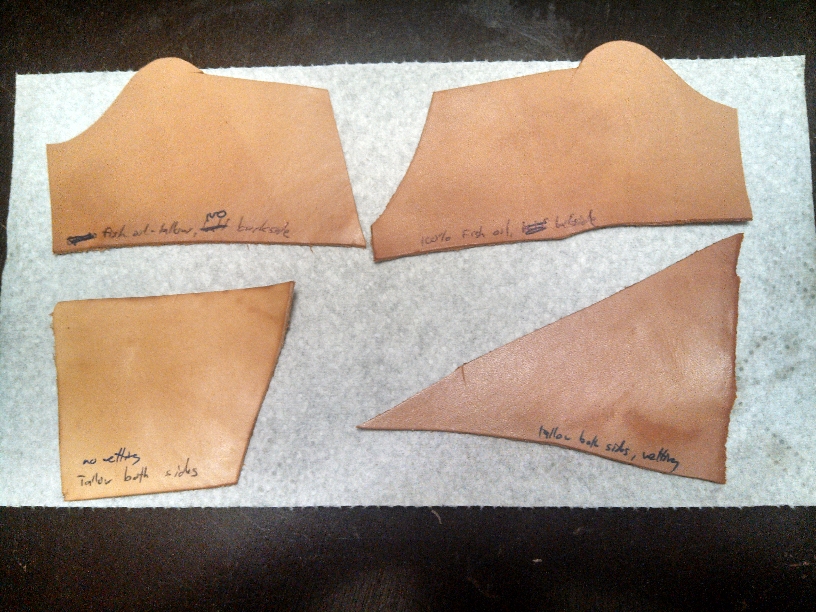

Anyhow, I started the process last night on some undyed vegetable tanned leather. Here is the first shot of the process.

I applied cod liver oil to wet leather on two pieces, one on just the front (upper left), and one on both front and back (upper right). I gave each a couple of light rubbings, until there was a bit of a sheen of oil left on the grain of the leather. On two other pieces, I decided to just use tallow. One was completely dry (lower left), and the other wet (lower right). I used tallow on both grain and flesh for both. Instantly, I was surprised at how supple the dry leather became after rubbing in the tallow. Now that they’re dry, I’ll check it out tonight and see how they feel. If there is a need for more fish oil, I’ll reapply, but thus far, I’m quite pleased with the way that the tallow feels.